The tears of a clone (12/19/00)

____________

Travolta has threatened a sequel to

Battlefield Earth, rumor now attaches the name of Ridley Scott to

Terminator Three, Terry Gilliam’s latest project is accursed, Meg Ryan is mulling over the idea of playing the lead in a Linda Lovelace biopic [presumably working with Nora Ephron will teach you a lot about suppressing the gag reflex], and Stallone’s mom’s psychic dogs are predicting a bright romantic future for newly-minted billionairess Anna Nicole Smith [so are mine.] But our aims this week are purely spiritual.

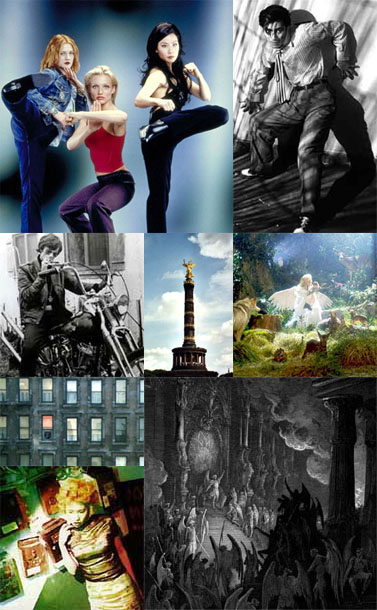

Charlie’s Angels. [McG, 2000; writers beyond number.]

Irresistable megaditz and wouldbe Dancing Fool Cameron Diaz, leatherclad dominatrix [but abominable cook] Lucy Liu, and producer/gigababe Drew Barrymore — so supremely confident of her ability to pull this one off that she allows her fabulously untalented boyfriend not one but two scenes herein — reprise the roles made famous by whatstheirnames in the late and now mysteriously lamented Seventies action/titillation series; accompanied by the new Bosley, Bill Murray; and assisted by a phenomenally talented assortment of effects wizards and martial arts choreographers and an army of writers whose willingness to hurl their bodies beneath the chariots of the studio Pharaohs must recall the sacrifices of the slaves who died to erect the Pyramids.

Of course, the Pyramids are impressive, and, in its own way, so is this scenario: after preliminary flourishes which serve to establish our heroines as daredevil Masters of Disguise, they converse by telephone with their invisible and mysterious employer, the eponymous Charlie [still the voice of John Forsythe], receiving the intelligence that computer zillionaire Tim Curry [here as always a guy who looks like he is twirling his mustachios whether he has them or not] is supposed to have kidnapped rival computer zillionaire Sam Rockwell in order to steal...something [as Hitchcock was always fond of pointing out, it never matters what it is, only that it is] — with which [dare I say it] he can rule the world. Bounding from the office sofa with girlish enthusiasm, they dance through a succession of undercover roles, imitating, variously, massage therapists, swank-party caterers, Formula One drivers, bellydancers, corporate consultants, ninja safecrackers, frog girls, and birthday-telegram singers decked out in Heidi outfits [this one was by itself worth the price of admission]; mimicking, the while [thanks to the expert wirework of Hong Kong import Corey Yuen], kung fu badasses; establishing, in the meantime, the relative innocence of Curry [who hams it up with admirable relish nonetheless] and the relative culpability of Rockwell and his all-too-slinky ExecVeep Kelly Lynch; and prancing through whole transplanted chapters of several recent action hits before the Grand Finale, a threeringcircus shootout in an entirely improbable clifftop fortress. — Though none of this quite achieves, say, the playful touch of the classic Doctor Who episodes — in which the writers would manage to steal the plots of two or three bad old scifi movies in a single halfhour — the authors do exhibit a certain lighthearted grace in their systematic plundering of the recent history of the action flick; and one need only imagine what Stallone would have done to a script like this to realize that it might have been much, much worse.

Critical opinion has been remarkably undivided regarding the merit of this opus; and, indeed, it is difficult to see how it could stir any deeper controversy than a dispute over the proper spelling of “babe-a-licious”. [I take no position.] But where else can you see a sumowrestling match between Bill Murray and Tim Curry? And wouldn’t it be great if Bill Gates and Larry Ellison took the hint and kidnapped one another? hopefully never to reappear. However though its remarkable success has prompted the usual speculations about the birth of a franchise, the penurious studio executives at Columbia have already indicated their reluctance to rehire the current Heroic [and, accordingly, Expensive] Trio for the sequel — as always, penny wise, pound foolish: if they think I’d sit through this again without Cameron Diaz and Drew Barrymore, they’re out of their minds. Even a worm has his pride. At least I think he has.

Fallen Angel. [John Quinn, 1997.]

Saxophones. A rainslicked city street, at night. As a couple of 1947 roadsters cruise by to set the period of the piece, we dissolve through the entrance of a seedy tavern to the interior, where amid a festive crowd in period costume hardbitten private investigator James Patrick Keefe is knocking them down at the end of the bar while delivering the kind of worldweary voiceover that makes you wish for an international moratorium on bad imitations of Raymond Chandler. Fortunately for the sensibilities of the audience, his ruminations are cut short by the appearance of the slinky female Oriental chauffeur of Rich Bitch Samantha Phillips [presumably on loan to the Playboy Entertainment Group from Andy Sidaris], who in an audience in the back of her limousine represents herself as the wife of a mobster who is planning to kill her to cash in her life insurance policy; and, though our hero doesn’t exactly fall for the story, naturally he can’t help but fall for her. Sure enough, after the requisite atmospheric peregrinations through seedy office, smoky nightclub, fleabitten hotel, urinestained shoeshine stand, lowlife racetrack, dark dank alley, and rundown poolhall, and some weirdly anachronistic scenes of bikiniwaxed babes with silicone-inflated hooters and collagen-swollen lips making out in the bathtub, he fucks her, she fucks him, by dint of the feral cunning of the femme fatale she gets away with the money, and by dint of the pure dumb luck of the shamus he gets away with his life. “I knew from the start a dame like her was trouble,” he says ruefully. And I knew from the start a flick like this would suck. Both of us will have to console ourselves with the knowledge that we got to see Samantha naked.

Fallen Angels. [Kar-wai Wong, 1995.]

Or, night creatures of Hong Kong: after a shootout goes bad, a strangely detached [indeed almost unselfconscious] professional assassin decides, uncharacteristically, to take the reins of his career into his own hands and retire; he informs his agent/assistant, a leatherskirted Dragon Lady in spike heels and fishnet stockings, by leaving her the message that she should play a certain song redolent of renunciation and loss on the jukebox of a club which they both frequent [though they never seem to meet.] She reacts to this indirect announcement, as usual, by masturbating furiously on the table next to her fax machine. Meanwhile a curiously sympathetic [but alarmingly eccentric and apparently mute] thief is falling for an unbalanced girl strangely unreceptive to his solicitations; presently, all paths cross. The action takes place in garishly green neonlit urban night interiors [clubs, malls, subway stations] and is captured by a near-fisheye wideangle lens that never seems to be more than a few inches from somebody’s face. An arresting essay in romantic obsession and alienation; is this the Chinese film noir?

A For Andromeda. [Michael Hayes, 1961; story and novel by Fred Hoyle.]

A sevenpart BBC series based upon a scenario written by the noted astrophysicist and more-than-occasional author [in his heyday referred to by envious colleagues as “Leonardo da Hoyle” — later knighted, but mysteriously unmentioned by the Swedish Academy when his collaborator Fowler was awarded the Nobel Prize for their joint work on the stellar nucleosynthesis of the chemical elements] about the detection of the first message from space by a harddrinking young radio astronomer whose brilliance ensures both the decipherment of the code and the alienation of his superiors — a shortsighted lot of selfserving bureaucrats who choose to ignore his warnings as they construct a massive supercomputer after the alien blueprints and, subsequently, synthesize a series of biological experiments which culminate in a beautiful girl [portrayed by the young Julie Christie] whose function [our hero warns] is that of a Trojan Horse. The later debt of

Contact,

Species, and even [one might argue] of Gibson’s

All Tomorrow’s Parties [which concludes with the incarnation of the network-resident synthetic female personality, the Idoru, via transmission by hypothetical nanofax] should be obvious. But Hoyle is deeper and more subtle — and, of course, got there far ahead of anyone else: indeed, the idea of a an alien intelligence invading the Earth not by physical intrusion but by sending instructions for its own construction seemed impossibly abstract at the time, and many people had difficulty understanding it. — After seeing

Species, I realized finally Hoyle’s mistake was the failure to make his alien heroine sufficiently buxom. Anyone interested in the exposition of scientific ideas should absorb this moral.

The Exterminating Angel. [Luis Buñuel, 1962.]

A titlecard displays the epigraph: “The best explanation of this film is that, from the standpoint of pure reason, it has no explanation.”

In an imposing mansion, in a Spanish-speaking country, in the not-too-distant past, servants prepare for a dinner party. Strangely apprehensive, they mutter nervously among themselves; by twos and threes they find contrived excuses to quit the scene, ignoring even threats of dismissal. They scurry out as the guests [about twenty of them] begin to arrive.

The invitees are an elegant lot: among them are a military man [the generic “Colonel”], an author, an architect, a doctor, a conductor, an actress, a diva, and the usual load of tightassed society women. They exchange elevated sentiments over the long dinner table, attended by the sole remaining [now strangely accidentprone] head waiter.

The host, for no apparent reason, repeats a toast.

The party repairs to an elegantly-appointed drawing room [paintings, sculptures, ornate mirrors, a grand piano] to converse after dinner.

And here, as the evening winds down and the camera moves from one of the guests to another, making their excuses to their host and preparing to leave, it gradually becomes apparent that some peculiar field of force has descended over the company, and that no one — albeit for no obvious reason — indeed in each case it almost seems to be by whim or accident — will actually depart.

Overcome by exhaustion, members of the party begin to doze off unselfconsciously on the couches; some even lie down on the floor. Those still standing remark their dismay, even disgust at this behavior. Nonetheless no one can seem to cross the invisible boundary that separates the drawingroom from the rest of the house.

Finally, past five in the morning, all fall asleep.

What follows once the new day dawns — the continuing ordeal of the partyguests, their rising panic, their mutual recrimination, the vigil without by the townspeople [Buñuel has the military ringed around the house; in contemporary America, it would be the media], the tacit agreements determining which closets are reserved for the toilet facilities and which for the trysts, the unrelieved stench, the religious observances [freemasonry revealed by signs and countersigns, fevered visions, prayers to Satan], the suicide pact of the young lovers, why one of the women declares her intention to insure herself against future recurrences of this situation by purchasing a washable rubber Virgin when she gets out, and what a bear and a couple of sheep are doing wandering around the house — passes for variation on the essential theme. Suffice it that though the party eventually escape, their liberation is quite as arbitrary as their incarceration; and is immediately qualified.

Others have realized the comic possibilities in dumping a boatload of the upper classes on, say, a desert island [with or without Gilligan and the Skipper]; but the idea of marooning them within sight of shore in a prison of their own devise is perniciously subtle, and savors of Sartre’s vision of Hell.

An entirely original investigation of the structure of unconscious compulsion; a devastating critique of bourgeois society. Undoubtedly a work of genius.

Date With An Angel. [Tom McLoughlin, 1987.]

Accidentprone celestial messenger Emmanuelle Beart trips over an errant satellite, busts a wing, and augers into the swimming pool of wouldbe composer Michael Knight; who, mortally hung over from the bachelor party at which he has attempted to reconcile himself to a forthcoming bourgeois marriage to uptight society bitch Phoebe Cates, takes a moment or two to settle into playing the role of Peter Pan nursing the world’s most beautiful Tinkerbell back to health. [I do believe in fairies. Honestly I do.] — The details of what follows [

Splash with feathers] aren’t terribly important; suffice it that animals love her, she develops a taste for French fries, and the soundtrack is an abomination. — It is, however, interesting to note that, had the story been set in the Fifties, she’d have been a Commie mole; in the Sixties, she’d have fallen in among hippies who would have saved her from contending agents of the CIA and the KGB; in the Seventies, she’d have been a hit at the disco; and in the Nineties, she’d have materialized from a hacker’s computer screen. But since Ms. Beart crashes into the Eighties, she lands in the set of

The Wedding Singer and everyone immediately starts trying to make a buck off her. Personally, I think I might have developed other ideas.

Angel Heart. [Alan Parker, 1987. From a novel by William Hjortsberg.]

Lowlife New York detective Harry Angel [Mickey Rourke] is called up into Harlem in 1955 to meet the mysterious and frightening Louis Cyphere [Robert De Niro], who represents himself as the former handler of a once-famous crooner named Johnny Favorite — maimed in the war, reduced to a vegetable state, placed in a sanitarium, and now disappeared. Services were performed for the missing singer, De Niro explains, and bills have come due; “certain collateral was involved.” Though Rourke agrees to take the case, it is plain that De Niro terrifies him; nor does it seem that he himself escaped the war without some devious form of brain damage, which manifests itself in vivid and strangely unsettling recurrent flashbacks — images of whirling fanblades, black nuns, a crowd carousing in a crowded square, a hotelroom with drawn blinds, circling spiral stairs, a descending elevator. Moreover everyone he can discover who knows something of the fate of Favorite — a junkie doctor [Michael Higgins], a jazz guitarist [Brownie McGhee], a palm reader [Charlotte Rampling] — is no sooner interrogated than murdered [indeed, subjected to some kind of heinous ritual slaughter] by parties unknown. Unnerved by his exposure to this ghastly violence, Rourke grows increasingly paranoiac and distraught: chickens terrify him; dogs attack him; he keeps staring at himself in broken mirrors. Following the trail from Harlem to New Orleans, he finds at last the daughter of Johnny’s longlost black mistress [Lisa Bonet] — a true voodoo child, fond of dancing naked in the woods covered with animal blood. — And here, presently, it becomes clear where Favorite is hidden, why De Niro pursues him, what Angel’s visions mean, and just who’s been fucking his own daughter; and why the elevator leads to Hell. — Dark, violent, and profoundly disturbing; something like Cornell Woolrich in voodoo. With

Blue Velvet, one of the great modern films noir.

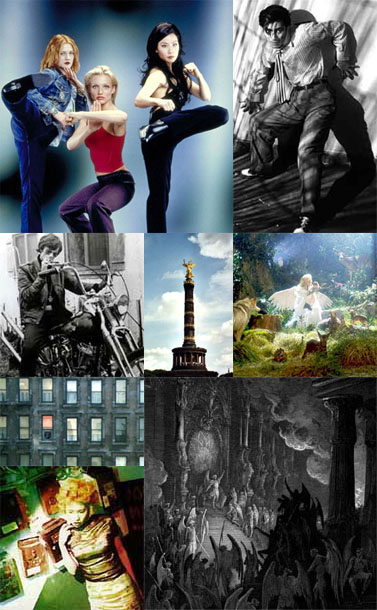

Wings Of Desire. [Der Himmel Über Berlin. Wim Wenders, 1987; screenplay by Wenders and Peter Handke.]

Invisible to all save children, angelic creatures Bruno Ganz and Otto Sander wander in long black overcoats through the streets of Berlin, dark capital of the dread history of the Twentieth century, listening in on the [remarkably poetic] streams-of-consciousness of its inhabitants — among them an elderly author, a teenage prostitute, an actor [Peter Falk, playing himself], a suicide — channelsurfing, as it were, among the inner lives of mortals. Gradually Ganz falls prey to the lure of temporality, and begins to yearn for the chance to step out of eternity into the flow of time, out of Being into Becoming — in Wenders’ visual metaphor, to descend from the abstract moral clarity of black and white into the messy particularity captured by color filmstock. He wants weight, wind, dirt: “to come home after a long day like Philip Marlowe, and feed the cat” — to have the thrill of discovery, not to know it all and to have known it all all along — no longer simply to observe, but to participate [doesn’t this seems like the desire of the critic to work on the other side of the camera? or perhaps the traditional anxiety of the artist over his detachment from a life of action] — to bleed, shiver, learn the names of the colors, mingle with beatniks, drink coffee, smoke cigarettes, act not watch — descend into reality and [are angels voyeurs then?] cop a feel off trapeze artist Solveig Dommartin. Presently he gets his wish, enters into history, and doffs his austere overcoat in favor of a loudly-checked jacket which in itself says everything we need to know about the relief one must feel at being released from the burden of angelically perfect taste. — And gets the girl as well, of course; but why spoil any more of the story.

Wenders made the sequel

Faraway, So Close! [

In Weiter Ferne, So Nah!] in 1993 with the same cast, augmented by, among others, angel Nastassja Kinski [talk about typecasting] and mortals Willem Dafoe, Lou Reed, and [no shit] Mikhail Gorbachev. [There is a satisfying poetic justice in the way that the two films so neatly bookend the fall of the Wall; and it is, of course, appropriate that the man ultimately responsible for the liberation of Berlin should make a cameo appearance.]

This last begins, incidentally, with an amazing shot: an iris-in on Sander [or his double], perched atop the statue [a wingéd Victory, of course] that crowns the Siegessaule in the center of the Tiergarten as the camera swoops in and circles; revealing, as it does, the whole of the city turning in the background. — This effect beautifully evokes the view the Immortals must have of the fallen world: a ball of light at a great distance, confined to a plane [one might say, projected on a screen]; seen as it were through the wrong end of the telescope.

Wenders was shamelessly ripped off by the Hollywood remake

City Of Angels. But accept no substitutes.

Lost Angel. [Roy Rowland, 1944.]

An infant abandoned on the steps of an orphanage is adopted by scientists determined to manufacture a prodigy; after six years, sure enough, she turns into pigtailed Übertyke Margaret O’Brien [John Stuart Mill was never so cute], who has mastered algebra, semantics, economics, Chinese, and the details of Napoleon’s Peninsular campaigns, but [reach for that hanky] just doesn’t know how to be a kid. Fortunately for her emotional development, she is discovered by a newspaper reporter trying to make a story out of her, and follows him home; compelling him, in due course, to adopt her, but not before a series of adventures in the real unscientific world of New York that acquaint her with a variety of Damon Runyan characters — boxers, torch singers, gangsters — though none so terrifying, we are meant to conclude, as the evil behaviorists whose mania for control has poisoned her childhood. — The fabulous irony, that the coldblooded manipulative skill of these fictional scientists must pale by comparison with that of the actual showbusiness mother who pushed a real sixyearold into playing this role in a motion picture, somehow goes unstated.

Drunken Angel. [Akira Kurosawa, 1948.]

Alcoholic doctor Takashi Shimura [obviously talented but compelled, somehow, to drown a sense of failure] while treating bulletwounded gangster Toshirô Mifune as an afterthought diagnoses tuberculosis; their subsequent relationship, which flickers in and out of focus with Mifune’s cycles of denial and Shimura’s erratic sobriety, forms the nominal matter of the picture — though the real subject [which Kurosawa cannot address directly] is the [graphically depicted] postwar degradation of Tokyo, a city which has obviously been bombed flat and left to choke in filth, garbage, and disease; it would, apparently, be a breach of propriety to state this explicitly, let alone to explain how and why it happened. [It is typical, for example, that the only indication of the occupation is a sign in English above the entrance to a club.] Still, the result is rare enough in its candor: an unsanitized Japanese specimen of the classic American gangster film — thugs, gamblers, swing bands, dancehall girls, and all. [And the women talk back, just as if they had the right to.]

As for the moral: Mifune, here a very young man, is magnetic and arresting; but it is the character of the doctor, who despite of or even because of his selfloathing is fearless and unfailingly energetic in the pursuit of his duty, that is, one must suspect, Kurosawa’s suggestion of a rolemodel for his countrymen.

Lucifer Rising. [Kenneth Anger, 1973.]

Another episode in the Anger Magick Lantern Cycle; or, what happens when you drop acid and read Aleister Crowley. [Honestly, in the days before Manson this was harmless fun.] — Some studies of vulcanism; a topless chick in an Egyptian-priestess outfit waving some magic wands around; hatching crocodiles; boiling mud; Egyptian ruins; either an imagined real or an imagined imagined ritual murder; the Moon; assorted poses against the backdrop of the Pyramids and the Sphinx; night procession of hooded figures bearing torches, having something to do with Stonehenge; a couple of Yeatsian towers; a few sacred circles and pentagrams; lightning on the plains; [my personal favorite] unsuccessfully-disguised footage of dancing girls arrayed around the Great God Tao [or whatever his name was] stolen from the Flash Gordon serials; and the descent of a flying saucer every bit as convincing as the ones you see in the home movies they show in the bullshit documentaries on the SciFi channel. — Music by among others Mick Jagger and Jimmy Page; it does sound like somebody’s album played backwards. — However impenetrable Anger’s intentions in most of this, one of the great mysteries of the Art Film, at least, can be cleared up herewith: the puzzle of why everything [and everyone] moves so slowly. Every shot, every motion, is painfully slow and impossibly deliberate, as if its significance [as contrasted, say, to a cream pie to the face or a smoking-rubber wheelie] were so vast and cosmic that the viewer should be given ten times the usual space and time to contemplate it. The explanation is simple: it’s because everyone [the cameraman included] is so fucking stoned. — These details one may garner from a perusal of the memoirs of the babe playing Lilith [hooded, cloaked, and smeared with imitation woad], Marianne Faithfull — famous as a singer herself, of course, and as Jagger’s girlfriend in the glory days of Swinging London; but here captured like a fly swimming slowly through thickening amber in the middle of her epochal smack addition. — Ms. Faithfull was discovered in the midSixties at a party in London by the Stones’ manager Andrew Loog Oldham; who signed her to a contract on the spot, muttering to himself the immortal phrase, “an angel with big tits.” Whatever the limits of Anger’s vision, Oldham’s, obviously, was boundless.

Paradise Lost. [John Milton, 1667/1674.]

Terminated with prejudice after leading an employee walkout, unrepentant miscreant Satan and his posse regroup in a tropical rental to plot their revenge. Determining to corrupt the unspoiled inhabitants of Eden, they dispatch Lucifer himself on an undercover mission to the newly-created Earth; after a vividly-imagined flight through the landscape of Chaos, he crashes the party, confuses the allegiance of the newly-minted Barbie and Ken dolls, and simultaneously precipitates their fall from grace and the birth of consciousness — thus establishing the principle that knowledge is sin, and leads to death; sure enough, Fundamentalists have been as dumb as dirt ever since. — In the end, Adam and Eve take a walk: fallen angels meet fallen arches. I loved the thing with the snake.

Roger Corman on his difficulties making

The Wild Angels [1966] — the exploitation classic which introduced the Hell’s Angels to the drivein audience and the director to the mechanical failings of Harleys: “We were always sitting and waiting for the damned bikes to be repaired, and I said to one of them [the bikers]: ‘Look, I understand what you guys do. You come into town. You beat up the men, you rape the women, you steal from the stores, the police come charging after you, you run to your choppers, and you know the fucking things aren’t going to start. What do you do then?’...‘They start, they start,’ they mumbled. ‘Bad luck, that’s all.’”

____________The girl with electroscope thighs (12/14/00)