A bovinity that shapes our ends (3/30/01)

____________

Time Regained. [Le Temps Retrouvé (d’apre l’œvre de Marcel Proust). Raoul Ruiz, 1999.]

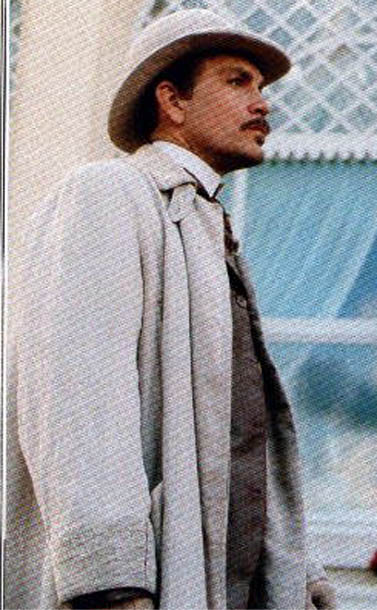

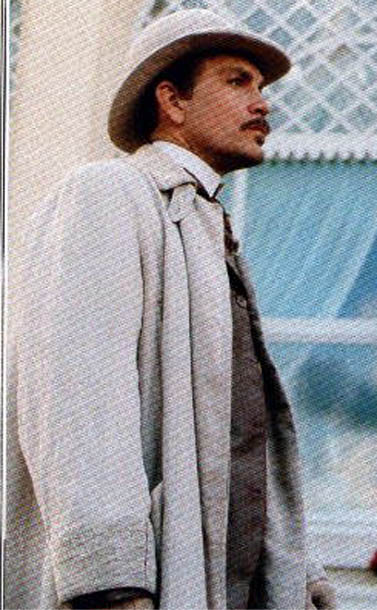

The credits run over a goldenlit shot of a flowing stream; the concluding shot exhibits the ocean. In between Marcello Mazzarella, Emmanuelle Beart, Catherine Deneuve, and John Malkovich debate the nature of Time, the disintegration of the linear text, the propriety of playing Beethoven at a Parisian social function in wartime, and the therapeutic virtues of getting whipped by cute guys in uniform. The results are mixed.

The story, like

Reservoir Dogs, begins near its end: the dying writer [Proust/Mazzarella], not actually gutshot but certainly sounding like it, dictates from his bed; attempting with a last obsessive burst of concentration to make sense of his life before it ends — or, to be absolutely precise, to make sense of his life [and thus render it Art with a capital alpha] as it ends.

It is the conceit of the project that he should be able to compose his memories into an organization that reflects their natural order — their structure as seen sub specie aeternitatis, like Vaughan’s vision of Eternity — and that this natural ordering should not necessarily be congruent with the simple-minded scheme suggested by the literal order of events; that though Time may be something like a stream or an oceanic receptacle, the true pattern of things is something more like that of a very complicated web document with a lot of hyperlinks in it.

Translated into the language of the cinema, this means that the narrative should be presented as a network of flashbacks; that characters should dissolve into one another [actually they ought to morph, but apparently this trick still lies beyond the technical capabilities of French cinema]; that there should be abrupt associative transitions between situations and eras; that the sight of an advertisement may transport Marcel instantaneously back to his childhood, and that something equally arbitrary [but, guess what, there is no such thing as chance] may carry him back [or elsewhere]; that the Ghost of Christmas Present should invariably invoke the Ghosts of Christmas Past and Yet To Come. Thus we have metaphysical assurance of the indivisibility of the Three Amigos.

A Proustian narrative, in other words, should look a lot like one of Tarantino’s; making it rather a disappointment that this one does not. Marcel’s idea of action is, alas, deficient: though it would be a vast relief if he ever actually knocked over a bank — or, in view of the fact that the center of gravity of this fragmented narrative lies somewhere during the First World War, took a cab to the front and fired a few shots at the Germans — his life instead, for curious reasons of social determinism, consists mainly of putting on starched collars and going to dinner parties where he hangs out with a lot of people who bore the hell out of him because he can see through them at a glance. [Lots of servants. Lots of junk art: statues, paintings, trinkets, bricabrac. Lots of cheesy pseudoclassical architecture. Lots of wallpaper. Apparently this was the Age of Wallpaper.] Since he is rather inappropriately gifted with an acute intellect and prodigious powers of observation [Sherlock Holmes becalmed among the Four Hundred], his air of decadent languor is clearly less a pose than the result of asphyxiating ennui. But an abrupt departure from the drawing rooms of Paris for a career as a consulting detective or as one of Sergeant Fury’s Howling Commandos seems out of the question. In fact, were it not for the occasional blackout or bombardment, and Marcel’s occasional expeditions to a male brothel where the [wildly various] sexual propensities of war heroes are acted out, it would be difficult for someone moving in his orbit to know there was a war at all. — The surreal contrast between the world of the drawing rooms and the world of the war is, in fact, so pronounced that even the members of the upper classes begin to remark it; though naturally only one or two go so far as to abandon their lives of privilege, enlist, and [predictably] get killed. [The suggestion that these one or two casualties have some special significance, measured against a conflict which slaughtered an entire generation is, weird but true, the most convincing evidence of the isolation of the upper classes from reality.] We see a fashion show with designs based on military themes; we hear complaints from the attendees when the pianist at a dinner party — no doubt some kind of Bolshevik — plays Beethoven. [“No,” says Ms. Deneuve with a smile, cocking her head to listen: “Schumann.”] It must be difficult to get good help, with so many in the trenches. Occasionally the lights go out. War is hell.

Presently the strain of reconciling these contradictions overcomes him, and Marcel retires to a sanitarium for the duration; emerging after the Armistice to discover his friends subtly altered [and not for the better], but his world, apparently — and this is strangest of all — not changed in the slightest. — Even Proust must find this depressing; he despairs of literature. We recognize even in this purportedly shapeless storyline the familiar fourth-act crisis. — But presently our hero is reconciled with his talent and his sense of smell; and, though there’s no chase, no shootout, and no last-minute rescue, something, perhaps, is saved after all. There is a certain familiar satisfaction in the conclusion.

Perhaps smell is just the problem here. Proust famously found the nonlinearity of experience best illustrated by odors, which, at least subjectively, seem to have the power to connect the present directly with the past; to recall childhood memories more rapidly [and one must hope more faithfully] than hypnotic suggestion. And it has often been remarked, for instance, that the classical view of epistemology [with which the author is trying to pick a fight] is largely the product of unquestioned assumptions about the primacy of vision. — The world would seem very different if we whistled it; as Marcel himself remarks herein, improvising a little essay on the idea of the leitmotif and the significance of the repeated phrase when a lady friend complains about the repetitiveness of one of his favorite composers. [Proust obviously would have loved the Ramones.] — Thus Thomas Mann claimed to have derived his own [very elaborate] system of correspondences in

The Magic Mountain from the example of Wagner.

But film doesn’t stink, at least if Joe Eszterhas didn’t write it; and this is supposed to be a movie. — Movies are, by definition, visual: they tell stories in pictures. And though every idea we find in Proust did, eventually, find its way into the cinema, each one had to be reinvented; and, actually, improved in the process. The vision of Proust is solipsistic: the correspondences are all internal, as if the hypertext could only link to itself. The vision of the cinema, if not precisely objective, nonetheless synthesizes multiple points of view: correspondences are established between several narratives [and several narrators] at once; it suggests, even if it cannot provide it exactly, the perspective of the eye of God. Actions and events are associated with one another even if they do not lie exclusively within the experience of a single protagonist. [Moreover, there is always something forced and unnatural about an attempted singularity of perspective; as evidenced by experiments like Robert Montgomery’s

The Lady In The Lake.] — One might think, for example, of the beautiful dissolve in Tykwer’s

Winter Sleepers between two still-unrelated characters, male and female, smoking cigarettes: as one exhales, the other inhales. [Later, naturally, they become involved.] — Nor should there in principle be a distinction between associative hyperlinks between events in a single writer’s life, or events in two soon-to-be-related characters’ lives, and correspondences between events separated by decades, generations, or geologic eras; the dreams of the world-soul [if you will] can take any shape, and take place on any scale. — This is the point, after all, of the most famous and audacious of all cinematic match-cuts: Kubrick’s dissolve from the spinning thigh-bone of the antelope to the spaceshuttle falling toward its docking station, which summarizes in a single associative conjunction the nature of tools. — Marcel, on the other hand, doesn’t get to ancient Egypt to investigate the invention of papyrus; in fact, so far as I can discern, he never gets as far as Marseilles.

In sum: nothing happens [and nothing is supposed to happen], the flick looks cheap [I’m starting to think there’s no cinematographer in all of France good enough to shoot a Guns’n’Roses video][Luc Besson doesn’t count], and it’s pretty rough sledding trying to get through a movie with so many Margaret Dumonts and no Groucho. — On the other hand, how can you resist a French art movie with Malkovich as a decadent aristocrat, Emmanuelle Beart as the babe who turns the head even of Proust, and the apparently ageless Catherine Deneuve as the unmoved mover of their social world? If only they’d thrown in a carchase.

“So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past.” Oh, you bet your ass.

____________Things go better with coke (3/28/01)