Rocket scientists (8/4/00)

____________

Onetime bigshot screenwriter Joe Eszterhas, his career in a tailspin after the ungenerous reception of

Showgirls and

Burn Hollywood Burn, has taken the writer’s last recourse and penned a tell-all expose of the seamy side of Tinseltown; though, fearing that his merciless delineation of the characters of Michael Douglas, Sharon Stone, et alia may prove actionable, he is said to have adopted the device of

Primary Colors and clothed the naked truth with a thin fabric of fictionalization. — Titled, apparently,

Hollywood Rhapsody [presumably because

Beyond The Valley Of The Dolls was already taken]; coming soon to a supermarket near you. I can hardly wait.

Ms. Stone, in the meantime, has agreed in principle to

Basic Instinct Two; something tells me Eszterhas will not be providing the script.

Meanwhile, back at the multiplex:

Me, Myself, And Irene. [Farrelly Brothers, 2000.]

An Evil Twin plot that represents roughly the geometric mean of

MI2 and

Fight Club: after decades of repression by the patsy without, the inner psycho in Rhode Island State Trooper Jim Carrey erupts in a moment of stress and the two halves of his personality contend for the hand of witness-in-peril Renée Zellwegger as they flee the wrath of an improbable alliance of cops, Ivy League mobsters, real estate developers, and zombies from the gates of hell [it was something like that]; this necessitating [naturally] a variety of ancillary observations on dwarves versed in the martial arts, sausages, the sanctity of the confessional, the propriety of whacking off over a mugshot, bugs, dead cows, the difficulty of pissing with a hardon, nursing mothers, albinos, the use of the dildo as blackjack, and, of course, multiple personality disorders. — Is it true about black guys and quantum mechanics? Or, as Carrey says of the Zeppelins popping out of a young lady’s blouse: Oh, the humanity.

The Straight Story. [David Lynch, 1999. Written by John Roach and Mary Sweeney.]

The auteur of

Blue Velvet removes yet another mask, and this time reveals himself to be Garrison Keillor — and, like Keillor’s stories, this one is mostly true: cantankerous old Iowan geezer Alvin Straight [Richard Farnsworth], himself suffering from a degenerative hip condition and incipient emphysema, receives word his brother in Wisconsin [who else but Harry Dean Stanton] has suffered a stroke; determined to mend fences with his estranged sibling, to whom he hasn’t spoken in ten years, he decides to do ritual penance by negotiating the three hundred fifty miles that separate them. Since diabetes has rendered him nearly blind, he has no car and cannot, in the ordinary sense, drive; undaunted, he grafts a homespun camper onto the back of a John Deere tractor-mower and, over the stuttering protests of daughter Sissy Spacek, sets off on a pilgrimage across America’s heartland. — On this premise Lynch constructs an entirely antiCalifornian motion picture, one embued with an almost Heideggarian sense of communion with nature [I think I want the German for “being-among-the-cornfields”] — in which most of the characters are old, and none are pretty; in which no one seems to have sexual intercourse, but everyone seems to have children; in which no highway spans more than a couple of lanes, and no business district more than a couple of blocks; in which [in pointed contrast to the recent exploits of Nicolas Cage] the hero’s velocity never exceeds one or two miles an hour; and in which the closest approach to action/adventure is an utterly static but profoundly moving scene in a bar in which Farnsworth and another lifebattered old fart, with nary the hint of a flashback, weep unashamedly into their beers as they recall their travails in the campaign against the Germans. — I am long past the point at which I can be surprised by Lynch’s originality, but it’s still remarkable just how good he can be, when that alone is his purpose. — A great motion picture.

Diary Of A Lost Girl. [G. W. Pabst, 1929.]

An unscrupulous business associate of a respectable bourgeois family takes predatory advantage of innocent young daughter of the household Louise Brooks; since a deficient spermcount is never a problem in these morality plays, she promptly bears issue, and, when an evil governess [who has, ironically, hosed her way into a position of influence] whispers ill counsel into the ear of Paterfamilias, the infant is transmitted to a cutrate orphanage and Lousie is packed off to a reform school run by protoNazis. Here she takes her place at a long table of terrified schoolgirls who, like galley slaves, lift soupspoons to their mouths in robotic synchronization as Boss Woman [in the conductor’s place] beats metronomic time. Busting out when the inmates riot, she attempts to recover possession of her child but discovers it has expired from neglect; desolate, she takes refuge in a house of ill repute, where though she adopts the uniform of the flapper she protests her intent to preserve her only slightly-compromised virtue. Alas, somebody hands her a glass of champagne, and before she knows it the Twenties are roaring in her ears; when she comes to she discovers to her chagrin that she has been ravished again — though of course this time the gentleman has had the good grace to pay her; shrugging, she accepts her destiny. From here only a few more twists of the plot and several occasions of magnanimous refusal to take revenge on those who have wronged her suffice to advance Louise from hooker with a heart of gold to wife of a millionaire Count; and, remarkably, at that inevitable culminating Velma Vilento moment when she is unmasked as a fallen woman who has attained social position, she disdains evasion of the facts of her past and faces down a host of blackmailing harpies by dint of sheer nobility of character. — A kind of Weimar rewrite of

Way Down East; though of course Griffith never would have allowed Lillian Gish to take up prostitution. — Pabst doesn’t have a wow finish like Griffith’s chase over the ice, of course, but does evince a gift for striking visual imagery comparable even to Hitchcock or the early Lang.

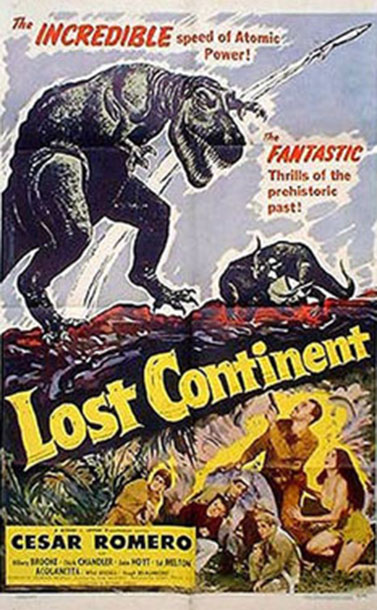

The Lost Continent. [Samuel Newfield, 1951.]

When an experimental nuclear rocket sails off their radars to the ends of the Earth, the Air Force dispatches intrepid flyboy Cesar Romero and a planeload of German-accented scientists to the terra incognita of the South Pacific to find it; crashlanding on a Polynesian island where mysterious radiations seem inimical to electronics, they are directed by a native bimbo in a grass skirt toward a taboo Sacred Mountain whose vertical cliffs are thick with poisonous fogs and whose summiting plateau harbors giant lizards and is bathed in a weird green light which is apparently supposed to remind you of what gamma rays did to the Incredible Hulk. Sure enough, they find the rocket; but somehow the act of yanking the recorder out of the nosecone triggers a volcanic eruption, and they escape in dugout canoes in the nick of time as everything sinks beneath the waves. When I figure this one out, I’ll let you know.

Shaft. [John Singleton, 2000; written (mostly) by Richard Price.]

Vexed beyond measure when a racist scumbag spoiledrichboy murderer [none other than the American Psycho himself, Christian Bale] skips bail and evades justice, police detective John Shaft the Second [Samuel Jackson] takes the advice of his uncle John Shaft the First [the redoubtable Richard Roundtree] and tells the Man, the Department, and the System to take their job and shove it; following which act of self-liberation he runs wild in the streets of the Big Apple shooting it out with the gangs of intermediaries the script keeps interposing between him and the one witness who can put the brat away. In this enterprise he is assisted, naturally, by the Good Guys, and tramples on the rights privileges feelings and sensitive corns of the Bad Guys — which is, I suppose, as it should be, though it proves unusually difficult to tell the black from the white hats, thanks to an inconsistent coding scheme that alternates political correctness with the cheapest kind of racist stereotyping: black guys are cool, except for the worthless hiphop gangsta niggaz; Latinos are cool, except for the Dominican drugdealing greasy spics; cops are noble warriors for justice, except for the cocksuckers on the take; only affluent Wasps and the amoral lawyers who preserve them in their privileged coigns of vantage can be trusted always to be evil. — But what the hell. Someone has to be trusted to waste scumbags indiscriminately, and it might as well be Samuel Jackson and Vanessa Williams. — Silly, but a pleasure to watch from the first tones of the wah-wah pedal to the closing credits; I read the very favorable audience reaction as an indication of how nostalgic people have grown about the golden age of the driveins. Indeed, the one thing that seemed to be missing was a

Planet of the Apes movie to fill out the double feature. But rest assured Burton is working on it.

Battlefield Earth. [Roger Christian, 2000. Written by Corey Mandell and J. David Shapiro; from an abominable novel by L. Ron Hubbard.]

A thousand years after the conquest of the Earth by the evil race of Psychlos, a ragged tribe of survivors hiding in the remote wilderness of the Rocky Mountains [picture Cro-Magnons clad in skins who inexplicably possess Hollywood teeth] pause during the ritual contemplation of their expository cavepaintings to expell rebellious youth Jonnie Goodboy Tyler — who, denouncing the smallminded cowardice of his elders in words familiar to all of us from a thousand earlier rite-of-passage pictures, leaps onto his horse and rides forth into the world beyond to seek the truth behind the legends of the conquerors. A mere mouthful of popcorn later he happens on a ruined amusement park which must undoubtedly be the work of the fallen gods, and no more than a couple of swallows after that he’s seized by hovercraft which fairly reek of alien menace and hauled off to the remains of Denver to pursue a rewarding career as a slave laborer. Here posed amid some striking CGI matte paintings he meets the principal representatives of the race of conquerors [John Travolta and Forest Whitaker, dressed for success in slimy evil-alien garb and sporting very bad unHollywood teeth], who are explained to be quasiSpanish conquistadors preoccupied with amassing plunder and scheming incessantly to stab one another in the back [referred to internally as employing/exerting “leverage”] so they can get their butts off this stinking colonial rock and back to “the Home Office” — which, naturally, several hundred commentators speculated must be in Milwaukee. Seeing in Jonnie an unusually bright animal whom they may exploit to increase the output of their gold mines, they plug him into an educational engine which [in keeping with the law of unanticipated consequences] teaches him enough about mathematics and the physical sciences to lead a revolt. — In short, another of those heroic-resistance-to-alien-tyranny stories, once a staple of the genre; doubtless inspired by historical precedents like the brilliant military campaign of Crazy Horse that drove the white man out of North America.

It should be explained about L. Ron Hubbard that, long before he decided to reinvent psychiatry for his personal profit, he was a very prolific science fiction writer in the golden age of the pulps; that the pulps paid by the word; and that this economic environment encouraged the evolution of a breed of artist who could type faster than he could think [admittedly not always difficult] and then con an editor into buying all of it. This does not guarantee the development of a good prose style: thus the original of this story was a gigantic pulp novel of about a thousand pages filled with vacuously repetitive dialogue and inane conceptualization; the gist of which has been faithfully transplanted into the screenplay, a scenario rich with banal prattle and burdened with annoying stylistic habits carried over from the magazine fiction of the Forties — e.g. dropping the word “planet” into the conversation several times a minute to give everything an air of astronomical verisimilitude. [Indeed, the most famous journal of the era was called

Planet Stories. One might compare the contemporary insistence on connoting network savvy by labelling every business plan with an entirely superfluous “dot com”.] — Alas, this is not the kind of inspired bad writing that produces lines people quote in wonderment decades later — like that, e.g., of Ed Wood: “You see? You see? Your stupid minds! Stupid! Stupid!” — “And remember, my friends, future events such as these will affect you in the future.” — “Saucers? You mean the kind from up there?” — etc., etc.

But, putting aside the political necessity of trying to minimize the unfortunate influence of the Church of Scientology, there isn’t much objective reason to dislike this movie [which is no dumber than

Independence Day, albeit without such overpowering effects]; save for the sad and silly fact [mysteriously unmentioned in the many bad notices, presumably because movie reviewers as a class have never held real jobs] that Travolta and Whitaker and their fellow Psychlos are clearly characters drawn from life: cackling idiots who zestfully screw all their underlings simply because they can; and then react with baffled astonishment when their superiors treat them in the same fashion. — Indeed, most of the organizations that I have had an opportunity to observe at close hand are not governed by considerations of productive efficiency or even by the profit motive, but by the same rules as one of those tribes of baboons in which nothing matters save who gets to buttfuck whom. Thus it seems peculiarly appropriate that the imprisoned humans should hang from the bars of their cages and scream like monkeys; and ironic that they should react so strongly to the protagonist’s stirring peroration attempting to rouse them to the emulation of the greatness of their ancestors. — “Free men built these cities!” he exclaims, as he gestures to the urban ruins all about them. — Guess again, Jonnie.

Steve Martin, in

The Man With Two Brains: “Ladies and gentlemen...I can envision a day when the brains of brilliant men will be kept alive in the bodies of dumb people!” Perhaps he had that backwards.

Later.

____________A prayer for Carroll Shelby (6/19/00)