Rock around the clock (10/24/03)

____________

Least appetizing trailer of recent weeks: for the forthcoming remake/reinterpretation of

The Alamo. In the unlikely event that I sit through this, you can bet that I’ll be rooting for the Mexicans.

Kill Bill. [Quentin Tarantino, 2003/2004.]

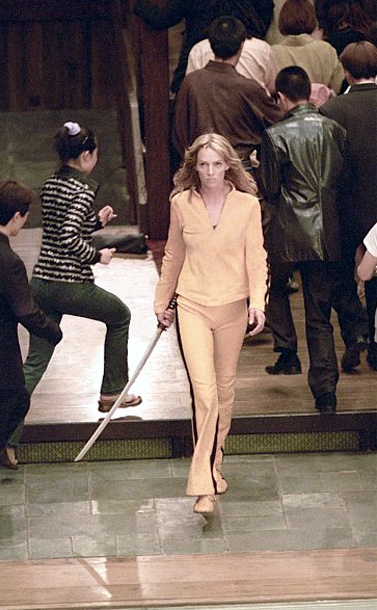

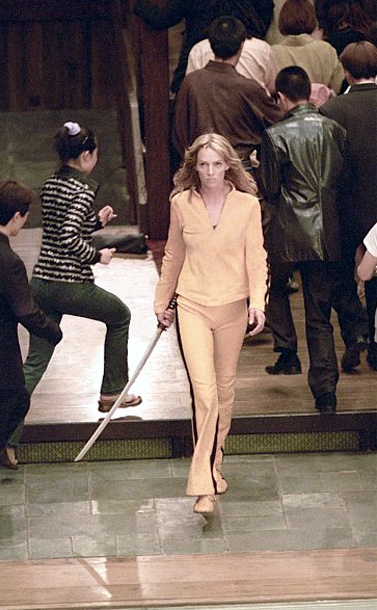

In a brief pause between the first and second acts of an epic three-act swordfight in a Tokyo restaurant [“The House of Blue Leaves”] which reduces a small army of masked and blackclad Yakuza neosamurai to a heap of twitching body parts in a midsized lake of very scarlet blood, Lucy Liu [holding the advantage on defense] and Uma Thurman [pressing the initiative on offense] smile coolly at one another and exchange a few pleasantries regarding Uma’s progress toward her objective of killing all of Lucy’s retainers and exacting a wildly melodramatic revenge upon Lucy herself; and conclude their dialogue by reciting in chorus the curious formula — passed off [in the screenplay] as a girlish ritual left over from their carefree days together as members of the Deadly Viper Assassination Squad — “Silly rabbit. Trix are for kids.”

This illustrates the glory and the misery of Quentin Tarantino.

The glory, because he has this marvelous absolute childlike possession of the furniture of his past, of every constituent brick of his mental architecture, every fragment of trivia, every banal scrap of melody and witless line of dialogue from every mindless television commercial, every twist of every plot of every lowbudget kung-fu chop-socky slugorama, every mannerism of every forgotten star who ever drained his pocket flask and lurched drunkenly across a drivein screen toward an assignation with a giant spider. Every ephemeral moment of every exhibition of every artifact of the wholly disposable culture that has grown like a mutant slime mold on the surface of our civilization, found its way onto film and into the medium of television, and been radiated outward into the empty vacuum of interstellar space, lives on in his imagination and can be instantly recalled; and no one, accordingly, can better resurrect the uncanny moments of unexpected beauty buried in this all-encompassing entropic dross that would otherwise be lost. His tastes are absolutely democratic, his vision thus catholic and universal.

The misery, because like Borges’ protagonist Funes, whose intelligence was erased by the terrifying perfection of his memory, he is not infrequently overwhelmed by the totality of his recollection, the completeness of his eidetic powers of recall, and cannot distinguish good from ill, significant from insignificant, the nugget of gold that is revealed when the shit is scraped from its surface from a lump of shit simpliciter. — He cannot

subtract. — In consequence his mental space is not arranged with the elegance of the Japanese garden to which Uma and Lucy repair for their final showdown, but in a random jumble, like the cluttered attic of the compulsive packrat; and his allusions display a distressing tendency to veer away from any semblance of relevance to his narrative purpose into a kind of junkyard fetishism of the found object.

Both the glory and the misery of the celebrated auteur are on display in this opus, the first of two installments of a long [when completed probably about three and a half hours] but unfailingly fascinating exercise in a classical form, the saga of revenge, whose cinematic avatars have in recent years included John Boorman’s

Point Blank and Alex Proyas’s

The Crow.

The conventions of this genre require that the protagonist, like Monte Cristo, return from death [or a convincing simulacrum thereof] to exact a terrible serial vengeance upon the conspirators who murdered him, hunting them down and dispatching them one by one: an avenging angel, remote, pitiless, and implacable. [Uma to Viveca Fox: “It’s mercy, compassion, and forgiveness I lack, not rationality.”]

And here indeed Ms. Thurman, [referred to as The Bride or Black Mamba, and not, for some reason known only to Tarantino, by the most authentic of the names on her fourteen passports, Beatrix Kiddo — in fact he insists on making a mystery of this and ostentatiously bleeping it out whenever someone utters it], represented as a member of a squad of assassins [Viveca Fox, Lucy Liu, Michael Madsen, Daryl Hannah — essentially the “Fox Force Five” of Pulp Fiction, and you can practically hear the quotation marks] led by her mentor and lover the eponymous Bill [David Carradine], having left the reservation and attempted to marry and retire when she discovered herself pregnant [with, we learn in the opening shot, Bill’s own child], has been executed by her peers along with nine innocent bystanders in a grisly massacre on her wedding day in an El Paso chapel, hugely gravid in a white gown; and though left for dead has miraculously survived, though the bullet in her head has left her in a coma that has lasted either four or five years, depending on which version of the story you believe.

Awaking suddenly by apparent descent of the Holy Spirit [the sting of a mosquito: either an inversion of Emily Dickinson, or, more likely, a reference to some biker flick no one else has ever heard of][the return of the avenger from the dead is always miraculous, suggesting divine intervention, and he/she is often — though not here — accompanied by a familiar or companion who represents the rooting interest of the gods in his/her success — e.g. the Crow itself, or the mysterious stranger who advises Lee Marvin], she wastes the attendant who has been cheerfully auctioning her body off to fellow narcophiliacs while her spirit wandered the empyrean, confiscates his garishly-appointed pickup [’the words “PUSSY WAGON” written along the flat-bed hatch door in a pimpy font’, the author specified, and the production designers were happy to oblige him], and sets out to send her erstwhile colleagues sequentially to hell.

The action is designed in strict accordance with the conventions of the Asian exploitation cinema: its authenticity is ensured by the guidance of the ubiquitous Yuen Wo Ping and the participation of the legendary Sonny Chiba, who forges Uma’s sword and delivers the requisite martial-arts-master’s lecture on the Way of the Samurai with formidable gravitas; and it is accompanied by self-consciously systematic abuse of what Tarantino refers to as the “SHAW BROTHERS ZOOM” into huge Sergio Leone gunfighter’s-stare two-eyeball closeups [the shot which most directly illustrates the plausibility of the conjecture that the widescreen aspect ratio was unconsciously chosen to match the spacing of the human eyes], a lot of obnoxiously loud spaghetti-western theme music [which, to be candid, I could have lived without], and lots and lots of wildly exaggerated comic-book violence [not, it should be emphasized, as bad as has been represented: it was little noted that the much-lamented violence of Pulp Fiction all took place offscreen, and the same to a considerable extent holds true here; the most gruesome moments are not so much revealed by the camera as implied by artfully composed quick-cut montage] — which, in the case of the flashback detailing Ms. Liu’s rise to the Yakuza throne, morphs quite literally into an elegant passage in anime — the characters mouthing, the while, many yards of the famous Tarantino dialogue — which, let’s be clear, does not represent the way the way these people would actually talk to one another [any more than a real circle of assassins would be so neatly accessorized with cute handles like “Cottonmouth” and “California Mountain Snake”], but rather the way that Tarantino talks to himself: the way that Tarantino talks when he’s trying to impress himself with his erudition, the way Tarantino talks when he’s trying to gross himself out, the way Tarantino talks when he’s trying to scare himself, the way Tarantino talks when he’s trying to sound black, und so weiter. Fortunately Tarantino is a great talker, and all this is entertaining as hell; but let’s not pretend that it represents some kind of breakthrough in verisimilitude.

In the course of these adventures the usually radiant Ms. Thurman [regarded by many, viz. Tarantino and myself, as the most beautiful woman in the world] though she inevitably emerges triumphant gets shot, stabbed, mauled, pummeled, raped, rolled in dirt and drenched with blood, and [in short] repeatedly gets the shit kicked out of her — which seems, actually, less some kind of sadomasochistic expression of an erotic obsession than the impulse of an eightyearold boy to beat up a pretty girl to show that he likes her; did Von Sternberg ever do this to Dietrich, after all? — But let’s not pry. What the author and the object of his desires do in the privacy of several thousand multiplexes should be their own business.

The details of character and place are as always brilliantly vivid: the hospital attendant’s pussy wagon and his tattooed knuckles a la Mitchum [“B.U.C.K.” on one hand, “F.U.C.K.” on the other], Ms. Fox’s suburban retirement in [a private cough behind the hand here] Pasadena, Chiba’s insubordinate assistant, Liu’s meticulously individuated posse of Yakuza badasses [featuring, e.g., the world’s deadliest Japanese schoolgirl]; and the familiar Tarantino device of shuffling the temporal order of the narrative and telling most of the story in flashback is exploited to very good effect [particularly in the second half of the story, as will subsequently appear.] — Coaching Uma and Lucy to speak their own dialogue in Japanese was an excellent idea; and is in itself, of course, a deeply-felt homage. — And, incidentally, readers of the screenplay who may have wondered whether “the most disgusting jar of Vaseline in the history of cinema” would live up to expectation will not be disappointed.

On the other hand, as noted above, there are a lot of weird false notes — calling “Revenge is a dish best served cold” an “old Klingon proverb”, e.g., or the way that Uma makes a list of her targets with a felt-tipped pen in a spiral notebook [Bill’s name last, and in red], and crosses them off when they have been dispatched: would she otherwise forget? [And what will she put on the seventy-nine pages she’ll have left over?] — The main thing that puzzles me, actually, is a casting issue: the Deadly Vipers should, logically, all be women; it looks as though Madsen was demoted from Chief to Indian when Tarantino was seized by the idea of casting David Carradine [a Seventies icon, of course, and this is typical] as Bill, and I’m having a hard time making sense of this decision. Perhaps the author’s wisdom will be clearer in the sequel.

The cinematography, the work of Oliver Stone’s right-hand man, Robert Richardson, is far better than in any previous Tarantino opus [

Pulp Fiction in particular had a deliberately cheesy look]; though it may be ironic that most viewers will recognize Richardson’s signature devices from

Natural Born Killers, which Tarantino wrote but later disavowed.

The martial arts choreography is excellent, though Yuen Wo Ping now gets so much work you have to wonder whether his product is being cheapened. Of course, Picasso also had a problem with being too prolific.

Qua action movie, Tarantino quite consciously set out to make a statement here, and indeed the results are impressive; though not, someone has to break it to him, as impressive as the work of his friend Robert Rodriguez, let alone the great Hong Kong masters like John Woo and Tsui Hark. — This is a gift, and you either have it or you don’t. — What Tarantino does have are gifts for plot, character, and dialogue, and they’re certainly apparent here. Quibbles aside, no one else can be as interesting, and the principal complaint you can make of the author of this film is that he doesn’t make more of them.

____________The happiest dog in the world (8/7/03)