Rocket science (1/15/03)

____________

Die Another Day. [Lee Tamahori, 2002.]

Bond reminds us once again why we’d all be happier if the British were still running the world: captured when a black op in North Korea is betrayed and goes south, our hero gets tossed into a dungeon and tortured by extremely professional specialists for the space of fourteen months — and, unkindest cut of all, discovers when his handlers finally swap him out that they think he’s been reprogrammed as some kind of Manchurian candidate, necessitating that he go off the reservation to try to track down the mole who sold him out. The quest leads, as the conventions of the franchise require, to a series of picturesque locales, including Hong Kong, Havana, London, and [after suspicion focuses on a diamond millionaire who seems rather too much larger than life] Iceland, and resolves itself in a grand finale [again on the embattled Korean peninsula] in which Bond dukes it out with the evil mastermind in an aerial command post while a giant orbiting laser burns a path through the DMZ toward general war, universal cataclysm, and the triumph of inadequate fashion sense.

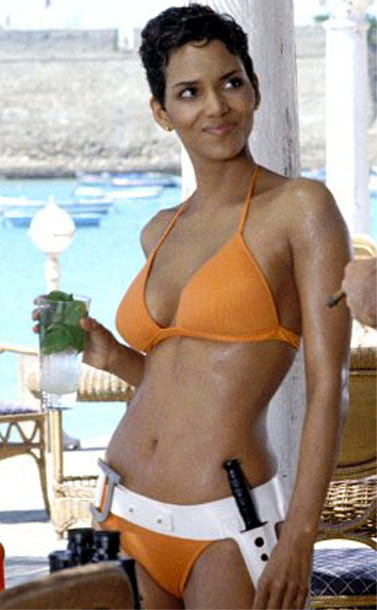

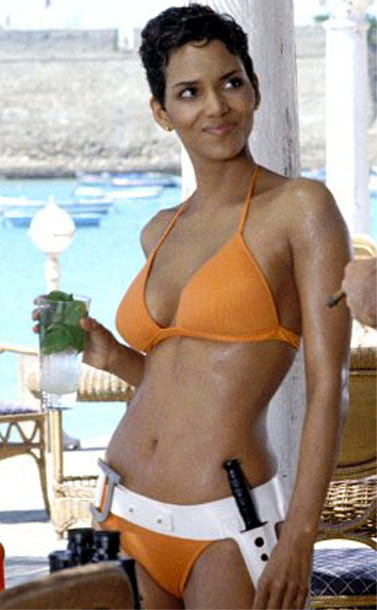

Herein we discover the standard elements, including: the villain with the glove [Toby Stephens] coded in some ingenious new fashion as inhuman [thanks to genetic reprogramming, he cannot sleep]; the henchman with a startling physical peculiarity [Rick Yune, with diamonds embedded by an explosion in one side of his face — nearly good enough for an old Dick Tracy baddie]; the opposed pair of gorgeous babes [Halle Berry and Rosamund Pike as either the bad good and good bad or good bad and bad good girls, you figure it out], one of whom, at least, does manage to hold out for a couple of minutes of screen time before she has sexual intercourse with our hero; the chases in unusual vehicles [military-issue hovercraft and some kind of rocket sled]; the real hightech toys [the VR trainer, cellphones transmitting images, PDAs adapted as controllers for satellites] and their parodies [the familiar multifunctional watch and a magical glass-shattering ultrasonic ring]; the reductio ad absurdum of the luxury car [an invisible Aston Martin]; the ultimate weapon [called Icarus: yes, this does turn night into day and is, therefore, the chariot of the sun, and, yes, it is driven by the offspring of a famous father, but, no, the old man isn’t really Daedalus; still, two out of three ain’t bad]; the penultimate weapon [very fancy body armor wired to dish out a hundred thousand volts]; the fight choreography [beginning to look derivative of Hong Kong, but there’s a great swordfight and a cleverly-designed punchout in which the participants have to keep dodging automated laserblasts]; the bad puns [also meted out to Halle and one or two of the bad guys]; the inspired production design [an ice palace in the Arctic which improves on Superman’s Fortress of Solitude]; the creative ways of wrecking flashy cars [here, by dropping them out of a plane]; the big stars in small parts [Madonna as a fencing master — I’ll bet she loved that corset — and Michael Madsen as a boss spook — as best I can recall the first guy in several episodes permitted to light a cigarette]; the filthy lucre [diamonds]; the glimpses of the lifestyles of the rich and famous [at nearly every turn: a rejuvenation clinic in the Carribean, a private club in London, a luxury hotel in Hong Kong, an exclusive reception in Iceland]; the amusing pseudoscientific patter [in re genetic engineering]; the jokes at the expense of traditional high culture [Sun Tzu and Gainsborough]; and a couple of absolutely priceless moments, viz., the opening night shots of Bond and his fellow Seals in black wetsuits surfing into the shores of North Korea [somebody must have seen the Surf Ninjas on the late show], and the improbable spectacle of a barefooted Bond, fresh from the dungeon in ragged hospital pajamas and looking just like Robinson Crusoe with unkempt full beard and long tangled hair, walking coolly into the lobby of an elegant Hong Kong hotel past a gawking horde of affluent Chinese in evening dress and demanding [and getting] the best suite in the house.

As for what didn’t belong: it is difficult to articulate precisely the way in which the Bond films have traditionally been “realistic”, but obviously this has always been the case: when Brosnan dived off the top of the Russian equivalent of Hoover Dam in

Goldeneye, it wasn’t Brosnan, and the dam wasn’t in Russia, but there was a real guy, a real dam, and a real fall at the end of a bungeecord recorded by real film in real cameras stationed a couple hundred feet away in the real fabric of three-dimensional space; when Roger Moore skied off the edge of a cliff in Austria in

The Spy Who Loved Me and flew away on a parachute sporting the Union Jack, it wasn’t Moore, and it wasn’t Austria, but the fact that they had to go to Greenland to find a cliff high enough and hire a world-class athlete to do the jump and pull the ripcord made the stunt all that much more impressive. And here though you know that the North Korean beaches are actually on Maui and that Spain is standing in for Havana and that the Aston Martin and the Jaguar aren’t really firing rockets at one another in that chase across the surface of that frozen lake in Iceland, you also know that this really is a lake in Iceland and that there really are a couple of madfool stunt drivers out powersliding around having a hell of a good time, and this is enough to ensure the suspension of disbelief, enough to ensure that the proposition “Brosnan/Bond is driving that Aston Martin” will pass the test for make-believe — and, by implication, carry much of the rest of the flick with it. But unfortunately you don’t believe for a moment that Halle Berry [or anyone at all] is actually doing a backflip off a sheer vertical cliff a couple hundred feet into the Carribean or that Brosnan is really surfing on a tidal wave chockfull of pack ice in the Arctic or that Brosnan and Berry are really bailing out of a crashing airplane; in fact all this looks unforgivably bogus. [The icepack-surfing sequence in particular looks even cheesier than the old AIP fakery posing Frankie and Annette in front of rolling breakers on the back-projection screen, which I would have thought impossible.] And the effect is [as Sartre would have said] one of bad faith. — The Bond movies have always represented the gold standard in stunt work — a standard embraced, for instance, by Jackie Chan, and adhered to faithfully by that master of the carchase John Frankenheimer — and have always made what many [e.g. Andre Bazin] have described as an essentially ethical choice about the relationship of film to reality — best explained, paradoxically, by a counterfactual conditional: if Werner Herzog had made

Twister, he would have chased real tornadoes. A departure from this standard is disturbing [and as it were debases the currency] because it suggests the kind of deviation from principle that presages the degeneration of a species or genre; or, in contemporary parlance, that the series is jumping the shark.

On the other hand, how else are you going to show a spacebased laser cutting a path through the minefields of the Korean DMZ? maybe they just need to hire some American effects houses and a real Hong Kong fight choreographer.

Or maybe they need hormone therapy, who knows. But what the hell, I loved that invisible car.

____________Walk like an Egyptian (12/22/02)