Holes in space (10/5/00)

____________

“You guys are really weird, you know that?” the girl remarks to the two nerds. “They’re not

weird!” the Monster exclaims — seizing the two geeks one in each paw and crushing them to his bosom with a fond embrace. “They’re

scientists!”

[

Frankenstein: The College Years.]

Almost Famous. [Cameron Crowe, 2000.]

Cameron Crowe’s beautiful autobiographical essay about his first tour on the road with a rock-and-roll band as a Boy Wonder stringer for the Rolling Stone — in which his alter ego Patrick Fugit by dint of talent luck and bullshit attracts the attention of the famous editor Ben Fong-Torres, acquires the assignment of following a group of rising stars [the fictional Stillwater] as they ride off to look for America, escapes the suffocating influence of his controlfreak mother [Frances McDormand], skips his high school graduation, and launches himself into an adventure that bounces him all over the Midwest in a tourbus, lands him in the exotic ports of Cleveland, Topeka, and New York, and places him finally on a chartered flight to hear the [memorably hilarious] last confessions of the band members as they prepare to auger into a cornfield in Tupelo; brooding, the while, over his portable typewriter as he tries to fathom the Deeper Significance of this roadtrip. For these were the now-distant days when sex was still safe, drugs were still plentiful, and rock and roll still meant something: when musicians were more than merely another species of the rich and famous; when there was a journalistic currency other than that of celebrity; and when the best writing in America appeared in the

Rolling Stone.

These delusions have long since evaporated; oddly enough it is only what once seemed most ephemeral, the sense of how much fun it all was, that remains. Oliver Stone may have found the war, but Cameron Crowe found the party. And since he may have been the only geek ever to have done so, his triumph sustains all of us.

So though obviously this is not the cinematic Bildungsroman that will make you forget

Platoon or

The 400 Blows, still, it’s one of the best rock and roll movies ever made. — With Philip Seymour Hoffman brilliant once again as Fugit/Crowe’s mentor the semilegendary rock critic Lester Bangs [pay particular attention to the speech in which he explicates the relationship of critic to rock musician as that of dweeb anthropologist to the tribes of the cool and the beautiful], Billy Crudup [actually better in the role than would have been the prior choices Cruise and Pitt] as the fledgling-star guitarist, and Kate Hudson as the leader of the Band Aids, Penny Lane. — When the riddle of the human genome has been finally deciphered, someone will be able to explain to me what makes Goldie Goldie, and how Kate inherited it; I want to hear how this is supposed to follow from protein folding.

Frankenstein’s Daughter. [Richard Cunha, 1958; written by H.E. Barrie.]

A high school girl figures out the mysterious laboratory assistant aiding her uncle in his scientific research is actually the last remaining scion of the Frankensteins: no wonder he’s been making eyes at her; he wants her body, and not necessarily all in one piece. Complications ensue. — An architectural quibble: I don’t recall that an attached dungeon was a standard option on the typical Fifties suburban home. But admittedly it should have been.

Nurse Betty. [Neil LaBute, 2000. Written by John Richards and James Flamberg.]

The screenwriter’s solution to the problem of an obsessive fixation on the Object of Desire is to act this fixation out through surrogates on whom [as it were by definition] such obsessions look good. — thus: Soapaddicted daydreamer Renée Zellwegger inadvertently witnesses the drug-related execution of her usedcarsalesman husband in the living room of their Kansas home; flipping out, she casts off the grim bonds that tie her to her rather sadly constrained life and her unfulfilling job as waitress in a roadside diner, hops into a Buick [ah, but it’s a Buick with a secret], and sets off for Los Angeles to unite herself with her imagined lover Greg Kinnear — star of a daytime melodrama which depicts him as a famous surgeon at a great metropolitan hospital, and, as usual, a guy who’s very impressed with his own importance. Along the way she dons a nurse’s uniform and begins to emanate a mysterious magnetic field which affects the internal compasses of everyone with whom she comes in contact, with the result that both the real and the imaginary hospital hire her, Kinnear falls for her in spite of himself, and even the hitmen on her trail [Morgan Freeman and Chris Rock] are diverted from their purpose by the force of her personality. The moral, plainly, is that you can get away with acting like a deranged stalker if you are Renée Zellwegger, World’s Cutest Human; but I don’t advise it for ordinary mortals.

One might contrast an old favorite, the 1971 feature

They Might Be Giants, in which George C. Scott played a paranoiac who thought he was Sherlock Holmes [and Joanne Woodward played a psychiatrist named Doctor Watson.] Somehow that worked beautifully; I think simply because it was so obvious that Sherlock Holmes need not himself have been any more than a paranoiac who thought that he was George C. Scott.

Hell’s Kitchen. [Tony Cinciripini, 1997.]

Errant slumchild Johnny “The Tombstone” Miles emerges from the joint after a stretch for armed robbery and attendant accidental homicide a sadder and wiser lad: his sainted mother has departed and left him with the sacred charge of looking after his ne’er-do-well little brother Stevie [mysteriously unavailable for comment and last seen flopping in the gutter sucking on a crack pipe]; moreover Tough Girl Angelina Jolie and her drunken-floozy mother Rosanna Arquette are determined to waste him for revenge. Fortunately he is taken under the wing of a slightly punchy Italian exboxer with cauliflower ears who trains him for a championship bout which he wins despite the insistence of a sleazy promoter who owns a string of strip clubs that he take a dive — and at this point [believe it or not] there are still a good forty minutes of clichéd situations to negotiate before the scenario comes to its conclusion: On The Waterfront Of New Jack City, or, Body And Yo Punk Bitch Soul. — The kind of movie that makes you want to reach out to that reckless miscreant with soft poetic eyes who accidentally wasted your little brother during that coke-frenzied orgy in which he was simultaneously popping your girlfriend and her mother, and, shucks, just give him a big hug. Or something like that.

Tycus. [John Patch, 2000. Written by Michael Goetz and Kevin Goetz.]

Tabloid reporter [and exmilitary martialarts badass] Peter Onorati stumbles across an underground city built by not-particularly-mad scientist Dennis Hopper to preserve humanity after the imminent collision of the Earth [the Moon, something] with an errant comet: yet another remake of

When Worlds Collide. Remarkably successful, probably because this is the kind of B-movie premise that works best in an actual B-movie; and not, say, a big-budget weepie like

Deep Impact. [Undoubtedly it would have been even better if Corman had made it in the Fifties for ten thousand dollars over the weekend from a script Jack Nicholson had written on acid.] — It would seem curious that the government is represented herein as rejecting Hopper’s predictions of doom without regard for the facts; were our elected representatives not engaged at present in an attempt to fire the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration en masse for finding evidence of global warming. Instead, it seems an added dash of realism.

Quiet Days In Hollywood. [Josef Rusnak, 1996.]

A hooker on the Sunset Strip who collects snapshots of celebrities gives a blowjob to a lookout for a gang of burglars whose girlfriend escapes when he gets whacked to wait lunch upon an obnoxious recording-industry lawyer who is sharing the favors of the wife of his boss who gets hit on at the health club by the dissolute gay boyfriend of the hooker’s favorite actor; when said boyfriend overdoses in the pool, her idol goes on a bender and ends up in her hotel room: Slacker on a shorter Rolodex. With Hilary Swank, Peter Dobson, Jake Busey, Meta Golding, Natasha Gregson Wagner, and B-movie vixen Tammy Parks as the redheaded flasher.

The Way Of The Gun. [Christopher McQuarrie, 2000.]

The directorial debut of the prodigious author of

The Usual Suspects: when two ne’erdowell gunsels [Ryan Phillippe and Benicio Del Toro, herein identified only as Parker and Longbaugh] trying to make donations at a fertility clinic happen across the identity of a surrogate mother [Juliette Lewis] about to give birth to the implanted child of a couple of specimens of the stinking rich, they form the notion of kidnapping the mother-to-be and holding the foetus for ransom; the plan succeeds, after a fashion, and they escape across the border to a picturesque From-Dusk-Till-Dawn motel from which they launch negotiations. But after a couple of acts of baroque variations have been interpolated between setup and dénouement, the relationships of the millionaire to the sources of his money, his wife to her bodyguard, the expectant mother to her doctor, the millionaire’s head of security to the expectant mother, the infant to its supposed parents, and of everyone left standing to the fifteen million dollars James Caan is hauling around in a gym bag have grown so complicated as to defy adequate resolution; though the concluding gunfight in a Mexican whorehouse [a meticulously staged homage to

Butch Cassidy] would certainly suffice in any ordinary circumstance.

So this isn’t as good as one might have hoped: there’s too much of what is obviously meant to be weighty philosophical dialogue, and McQuarrie is not Dostoevsky. On the other hand he exhibits a gift for the cinematic statement of paradox — e.g. in the carchase that goes at the pace of a slow walk, or for that matter in the very idea of an action movie about motherhood [one in which the most ghastly of the many bloodsoaked scenes is Juliette’s Caeserian section] — that has to remind you of Hitchcock. He’ll do better, given another chance. Meanwhile, check this out.

Woyzeck. [Werner Herzog, 1976.]

The fabulously deranged Klaus Kinski stars as the title character in this curiously theatrical production [“nach dem Bühnenfragment von Georg Büchner”] of the story of an apparently simpleminded soldier-Everyman stationed in a quaint postmedieval German village who is belittled by everyone: most particularly his Captain [who demeans him with absurd duties], the town Doctor [who performs witless pseudoscientific experiments upon him], and his wife [who cuckolds him with a handsome Drum-major.] Wandering in the woods beyond the city’s boundaries, however, he feels a nameless Presence in the world that speaks to him with a frightful voice, senses the possibility of transgression - what stands beyond the ground of Being, what happens “when Nature is over” — and, like a good German, having turned everything first into an occasion for metaphysical speculation [“Did the No cause the Yes, or the Yes the No?”] finds that in turn an occasion for grisly murder. — Somehow the sight of Kinski pressing his ear to the earth to hear the voices of the underworld and babbling about the figures toadstools form upon the ground [the cropcircles of the eighteenth century] made it obvious to me that Herzog is the only guy who could film Thomas Pynchon.

Cecil B. DeMented. [John Waters, 2000.]

An amusing demonstration of Waters’ determination to play his own Tim Burton to his own Ed Wood: a deranged terrorist collective of underground filmmakers [led by the ubiquitous Stephen Dorff] kidnap a Hollywood princess [Melanie Griffith, who here as in Woody Allen’s

Celebrity serves admirably as the hypostatization of the abstract Idea of the Movie Star] in order to employ her services, will she/nill she, in their ongoing improvisational motion picture project; sallying forth from their secret hideout [an abandoned theater in downtown Baltimore] they ride in the battered van that serves as their Batmobile to a succession of scenes at which they film one another delivering hilariously over-the-top speeches declaring the liberation of the art of film from the constraints and contrivances of the studios and the star system to terrified audiences of the cinematic bourgeois. Beyond its manifest resemblance to the life and work of the young Waters and his colleagues at Dreamland Productions, this is also a sort of film-geek remake of

Weekend [in fact I can’t figure out why Godard never made this movie himself], a nostalgic paean to the lost days of Sixties revolutionary fervor, and, obviously, an oblique commentary on the Patty Hearst kidnapping, rendered more piquant by the presence of Ms. Hearst herself [one of Waters’ current repertory company] in a supporting role. — With the usual jabs at heterosexuals, some amusing digs at multiplex culture [e.g., an audience sobbing helplessly at the theatrical release of

Patch Adams: The Director’s Cut], and a variety of acute observations on the cult of celebrity: by all means, let’s hear more about Mel Gibson’s cock. — Alicia Witt appears here in a role [expornoqueen turned artmovie vixen] that might better have been assigned to another occasional member of Waters’ repertory company, Traci Lords; and the gunfights haven’t enough Tarantino in them. But anybody who’d set himself on fire at a drivein for the sake of Art is all right by me.

Sergei Eisenstein. Autobiography. [Oleg Kovalov, 1996.]

A curious experiment which attempts to epitomize the career of the great Russian auteur by employing his own techniques — splicing together excerpts from his features of the Twenties and Thirties with samples from other avantgarde classics of the era [notably

Entr’acte (1924),

Kino-pravda (1925),

Geheimnisse einer Seele (1926), and

Un chien andalou (1929)] and documentary footage [including home movies of the master at work] according to the principles of dialectical montage: i.e., arranging a collision of images [thesis, antithesis] in an attempt to produce a [synthesized] whole greater than the sum of the parts. It is difficult, if not impossible, to explain this method verbally [and Eisenstein’s own writings would in any case be the best guide], but the idea is illustrated herein, for instance, by a passage which sums up the Age of Ford by intercutting some curious kind of industrial-film cartoon, a Busby Berkeley musical number, and the Moloch/machine-god episode from Lang’s

Metropolis. — We have also statements of the visual equations of spilled ink/spilled blood and bullets/semen, and many fascinating studies of waves, trees, childbirth, weapons, African tribesmen, nudist-camp ballet, cross-referential images of the French and Russian Revolutions, and lots and lots of very earnest Soviet industrial machinery [the contrast with Chaplin’s very funny capitalistic industrial machinery is pointed though unstated and as it were taken for granted.] A very minimal narrative voiceover is provided by a few dozen sentences from Eisenstein’s written memoirs. And all this without drugs.

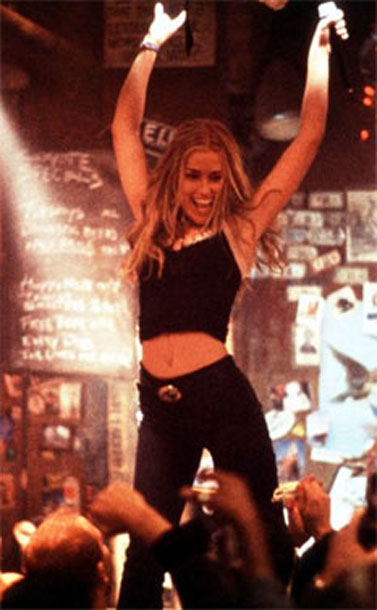

Coyote Ugly. [John Craig, 2K.]

It is Christmas in a town without pity. As a light snow falls on the seasonal decorations that adorn the streets and jolly elves in Santasuits ring bells on every corner soliciting softmoney contributions to political action committees, a lone waif dressed in rags looks wistfully through the window of a department store at an expensive garment draped upon the voluptuous form of a rubber mannequin. “Look at those hooters,” she sighs. “Just like Nikki Fritz. Someday... .” Her voice trails off. Gathering her tattered garments more closely about her against the bitter chill of the December breeze, she limps slowly down the sidewalk. She does not notice the man in the Santasuit muttering something into a cellular telephone. Passing the entrance to an alley, she hears a faint voice calling out for aid. Pausing, she looks both ways up and down the street; but it is now strangely empty, and no one is in sight. She turns to leave, but hears the voice again, more clearly now. “Help me,” it croaks. It seems the voice of an elderly man, crying for help. At the thought of a fellow human being alone, in pain, perhaps dying, she cannot hesitate. She enters the alley. Within the narrow passage the light is dim, crepuscular. Almost invisible, the figure of the old man, seemingly crushed and discarded, slumps against the wall beside a dumpster. “Help me,” he says. “It’s dragging in the dirt, and I just can’t get it up.” “What?” she asks, puzzled and now somewht apprehensive. “Can I help you?” “Sure, baby,” he cackles, stepping toward her. “Just take a look at this.” Ripping open his trenchcoat, he reveals an intricate pattern of ceremonial tattoos declaring him a prince of the Yakuza. A physically disgusting prince of the Yakuza. “Gaah,” she mutters. “What’s your name, sweetheart?” he asks as he advances. “Why...why...I don’t know!” she realizes. And swoons. She recovers consciousness in a dank stinking dungeon, chained to a wall splattered with blood and covered with politically-incorrect graffiti. Oil portraits of Jerry Bruckheimer hang everywhere around the room, protected by sheets of plastic. “What evil fate can have brought me here?” she wonders aloud. As if on cue there enter Ilsa, She-Wolf of the Heidelberg Bartending Academy, and her blonde-bimbo assistants, Gretchen and Brunhilda. “Welcome, my little cupcake,” Ilsa announces in a thick Teutonic accent. “It is time for your orientation.” Her assistants smile, strip to the waist, and begin to oil one anothers’ torsos. Ilsa flips a row of switches activating an alarming bank of electrical apparatus, attaches alligator clips to the most delicate portions of our heroine’s anatomy, and examines the readings on a bank of ammeters. “Interesting,” she murmurs. She adjusts a voltage. A pen begins to twitch up and down across a moving band of paper. “It is my contention that the female of the species can withstand more pain than the male,” she explains. “When I can prove this to the producers, it will undoubtedly result in larger grosses.” She throws a lever. A section of the wall revolves about a hidden axis, bringing a polka band into the cell. She makes a peremptory gesture with her riding crop. They break into song. Our heroine screams. Montage: other gruesome scenes of torture: leather whips, cattleprod dildos, repeated screenings of

Con Air. The pen jerks up and down upon the moving strip of paper, leaving a jagged trail behind it. Dreadful polka music. Dissolve through a ghastly accordian solo to a tavern scene: as a horde of drunken Yale fraternity men with duelling scars and promises of ambassadorships in the Bush administration wave beer mugs in the air and shout their approbation, a chorus line of dancing St. Pauli Girls decked out in peasant dresses cavort upon the top of the bar; our heroine among them. Swirling her skirts about her hips, she reveals unusually gaudy bloomers. The number concludes when a red 1969 GTO convertible hurtles through the front window with an explosion of glass and splintering timber, scattering the crowd and crushing several lawyers; a stunt driver staggers out and collapses, groaning “Tequila...tequila... .” Restoratives are applied. He gasps out a tale of a man wrongfully accused, prosecuted, incarcerated, busting out of jail and commencing an outlaw roadtrip through the Nevada desert with a girl and a gun which ends in armed robbery and a spectacular carchase; a barmaid takes notes for later review by studio executives. Having dived behind the bar to avoid possible gunfire, our heroine finds herself alone and unnoticed; crawling away from the others toward the egress, she notices that the wallsized mirror behind the liquorshelves has grown strangely translucent. Reaching out to touch it, she is amazed to discover that her hand goes into it as if into water; waves emanate in concentric rings from the point of entry. She crawls through the looking-glass to investigate. On the other side she finds a bizarre mirror-world in grainy black-and-white where the bar is a Parisian cafe, the fraternity boys are chainsmoking intellectuals who drink coffee and argue incessantly about the articulation of the noumenal self in the films of Jerry Lewis, and nobody understands money. Since everyone speaks French without subtitles, she has no idea what they are saying; she herself delivers a three-hour lecture on Dick Powell’s incarnation of the Cartesian ego in

Murder My Sweet without understanding anything that comes out of her mouth. Despairing, she crawls back through the looking-glass, finding the bar now empty save for a mysterious stranger seated by himself at a table in the back dressed in a black trenchcoat, wearing shades, and chewing on a wooden matchstick. “If you’re another tattooed flasher I’m going to rip your lungs out,” she warns. “No, baby,” he replies. “I’m the writer.” “All right,” she demands. “If you’re the writer then who am I?” He laughs easily. “The errant daughter of the wildcat oilman who disarms the biological weapons and saves the reformed carthief from the falling meteorite at the end of act two,” he says. “Played by Nikki Fritz.” “Oh yeah?” she says. “If I’m Nikki Fritz then what about these?” — ripping her shirt open and revealing to her own astonishment a pair of melons unmistakably those of Nikki herself. “But if I’m Nikki Fritz then you must be... .” “That’s right, baby. Leonardo Garbonzo.” A team of commandos burst in, weapons drawn. “Hands off that nipple ring,” their leader demands. Garbonzo sneers, whips out a forty-five, and points it at the head of an enormous stuffed animal. “Freeze!” he says. “Or the bunny gets it!” As each of the three dozen triggers of each of the three dozen guns now aimed at him makes a loudly audible click, with his free hand he dials a cell phone. “Quentin?” he asks quietly. “I have a problem with a standoff... .”

Later.

____________Laugh-a while you can, monkey boy (9/11/00)