Inside the beltway (8/29/97)

____________

Contact. [Robert Zemeckis, 1997.]

There’s an old cartoon that appeared in

Mad sometime during the Sixties: it depicted a scalyfaced monstrosity not dissimilar to the Creature from the Black Lagoon, just humanoid enough that it was easy to read its facial expression and realize it was pissed off past belief. The monster was framed by a television screen and apparently broadcasting a message of some kind. And what it was saying was this: “People of the planet Earth: We inhabitants of the planet Saturn applaud the scientific advances you have made which allow your television broadcasts to reach us here, eight hundred million miles from the Sun. Be advised, however, that if you continue to send us reruns of the

Gail Storm Show we will have no alternative but to DESTROY YOUR PLANET!”

And that’s why Jodie Foster goes to Vega. With: Matthew McConaughey as the boy she left behind her [when was the last time a theologian provided the love interest?]; David Morse as The Dead Father; John Hurt as a mad billionaire straight out of William Gibson; Tom Skerritt as a wicked academic; Rob Lowe as a loony preacher; James Woods and Angela Bassett as the Administration’s point men; and [after eliminating Sidney Poitier’s characterization in favor of Gumpkin cut-and-paste] Bill Clinton as the President. Story by Carl Sagan and Ann Druyan. Directed by Robert Zemeckis. In a summer fraught with space opera, a serious science fiction movie; is that a good thing?

The development of radar in the Second World War not only motivated a very considerable advance in short-wavelength radio technology, but acquainted many academics who had been conscripted into the war effort with its possibilities: in particular, though low-frequency radio waves are reflected by the ionosphere [a familiar aid to local transmission], the atmosphere is transparent at higher frequencies, and one can look out into space. [Or look back in. This was poignantly illustrated in 1946 when Signal Corps engineers first reached out to touch someone by bouncing radar waves off the face of the Moon.] Thus with the cessation of hostilities scientists began to investigate the possibilities of radio astronomy, and systematic efforts to map the skies at radio frequencies began which continue to this day. Though the most spectacular discoveries in this field, the quasistellar objects, are sources of galactic dimensions at cosmological distances, a parallel interest in local phenomena has grown up as a corollary to the realization that the Earth is itself, particularly since the beginning of television broadcasting, a radio source [albeit a dim one], and that one might, as a speculative venture, attempt a systematic search of the nearby stars for signals at radio frequencies, transmissions deliberate or accidental, as evidence of life or intelligence [but most likely of advertising] on other worlds.

The optimists who dominate the literature of this subject are not usually daunted by the fact that there are billions of places to look in the sky, and that the listener is twiddling the knobs on an infinite radio dial. Quite the contrary true believers insist, in the absence of any evidence for or against, that alien broadcasts will be deliberate and designed to be deciphered and almost certainly fixed on a wavelength with some simple and universal physical significance, e.g., one around fourteen hundred megahertz associated with radiative transitions in the hydrogen atom. Moreover they insist that alien intelligences are sure to be benign in their intentions, and that therefore it can do no harm to call attention to ourselves by attempting systematic broadcasts of our own on selected frequencies aimed at the likeliest candidates to harbor life among the nearby stars. [The giant dish at Arecibo, now a familiar face on the silver screen, could be heard at a distance of several thousand light-years.] — One must wonder whether these assumptions are reasonable. On the basis of human experience certainly they’re not. We don’t stand on the shores of California sending smokesignals to the natives of Borneo, reckoning that, when they’ve advanced enough to decipher them, we’ll welcome them into the international community: we’re right there in their faces digging the minerals out from under their feet, and swapping them television sets so that they can watch

Melrose Place. But it’s one of the unspoken axioms of the academic discussion that aliens will be better than we are: that they won’t have wars or the profit motive or that nagging problem with rectal itching; because, after all, they dwell among the heavens and are composed of a purer essence. — Perhaps this is reasonable, perhaps not. In the absence of any evidence, no one can say. — At any rate we’re looking. It isn’t likely that we’ll find anything. But if we did, it would change the world overnight.

And that is Sagan’s story: after a brief prelude which serves to introduce Jodie as a child whose parents die and leave her alone with her radios, we fastforward to the present, or roughly that [actually the part of the story’s argument that implies it’s 1988 has been held over from the novel, but let’s ignore it], and discover her a maverick radio astronomer in opposition to the establishment [Skerritt] who’s dug up unorthodox funding from the private sector [Hurt] to pursue a personal obsession with the search for extraterrestrial intelligence which leaves her no time for frivolities like romance [McConaughey]. Since this is a movie, her dedication is rewarded with the detection of a signal from Vega; which, it develops, is a response to [in fact is encoded as a modulation of a reproduction of] the first terrestrial television broadcasts. Embarrassingly enough these were German coverage of the 1936 Olympics, and exhibit Hitler and his entourage saluting the masses with raised-arm salutes; fortunately, the aliens don’t seem to have absorbed the deeper implications of the Nazi fashion statement, and reply not with exterminator rays but with detailed instructions for the construction of a mechanism, presumably some kind of interstellar catapult, into which, it presently develops, some daredevil human cannonball must drop herself to be launched across the cosmos. Much is made of the international search to find the most appropriate candidate, but inevitably Foster, after the discharge of a few subplots, is awarded the honor.

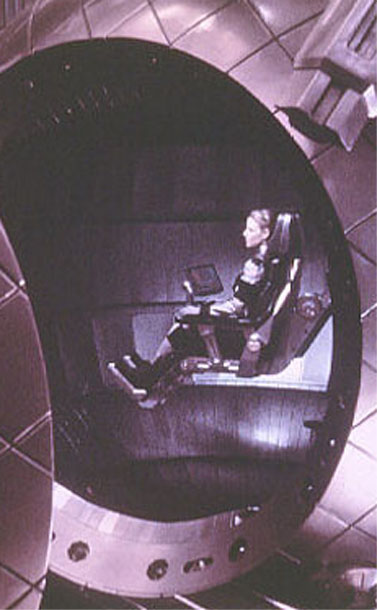

Vega, it develops, is a mere waystation, a local terminus of the galactic subway system; and, after rattling around inside her car for several hours while the automated dispatch system pops her in and out of a series of hyperspatial vortices, Jodie arrives at the center of the galaxy, drops into a virtual reality which looks just like Bora-Bora, is greeted by a benevolent alien dressed up as her father who says some nice patronizing things about the progress the species is making, and then drops back into her car and rides back.

Obviously that part of it had to be anticlimactic. But the denouement, alas, veers straight off the rails: the aliens, it turns out, have provided Jodie with no [direct] evidence of her journey, and the whole trip [moreover] seems to have taken place between ticks of the clock in local time; thus the entire visionary episode has exactly the empirical status of the Revelation of Saint John the Divine. This is an embarrassment when the inevitable investigatory committee grills her before an international television audience on her return, but ensures a more complete and satisfying reconciliation with man-of-faith McConaughey, not to mention the wholehearted adoration of the usual mobs of saucerworshippers who believe everything they read in the

Enquirer anyway.

On balance, therefore, Contact begs [unfavorable] comparison with a very different kind of movie, the extraordinary film

The Rapture [1991], written and directed by Michael Tolkin [author of

The Player] and starring Mimi Rogers, which tells the story of a sexually adventurous telephone operator who becomes a loonytunes fundamentalist, remakes her life around the conviction that the end of the world is at hand, goes out into the desert with her daughter to await the apocalypse, makes her version of the sacrifice of Abraham, is arrested and imprisoned, lapses into profound misery, and then [since her faith was indeed the true faith!] as the Four Horsemen ride about her is taken bodily to the shores of Heaven to argue with God His responsibility for human suffering. — Now, even this won’t bear comparison with Kierkegaard. But it’s a lot deeper than Sagan.

Still, in sum: a brilliantly detailed and wholly convincing portrayal of the way our elected representatives would react to a message from space; a somewhat-less-convincing explanation of the methods and motives of the beings who sent it [unfortunately “Einstein-Rosen wormhole” and “magic” mean about the same, and you might ask the Australian aborigine or the African gorilla about their encounters with more advanced and presumably benign civilizations]; a typically imperfect representation of the spirit of scientific research; and a pathetic rehash of the science-versus-religion debate of a kind that was tired cliche before the turn of the century; with, moreover, the consistent subtextual suggestion that the aliens are God and Spielberg their prophet.

But that isn’t what pisses me off. What pisses me off is the Hollywood portrayal of the scientist.

Let it pass that the boys in the lab look suspiciously like the boys in the van in

Twister: just the usual happy-go-lucky band of freaks and geeks, good enough to call upon when you need a tornado chased or a missile launched, but otherwise specimens of a lower social caste who can’t be taken seriously and must without question be kept carefully in their place. I’ll put up with that. In sharp distinction to the politicians in the movie, they look like they’re having fun; the fact that wealth, power, television exposure, and regular intercourse with starlets are the unquestioned perquisites of a different class is something that ought to be examined; but, that will have to be later.

No, the problem is Jodie. Obviously it’s dramatically convenient to invent a character such as hers whose parents were lost at a tender age; particularly convenient when the dramatic apogee of the story is a meeting with an alien clone of her father in the Ninth Sphere of the Empyrean. But it is insulting to connote, as this treatment inevitably does, that only someone whose relationships with other people had somehow suffered irremediable damage would ever turn to a scientific career; and not, say, write celebrity journalism for

People magazine like a normal person. It appears that the kind of pure scientific curiosity that Foster’s character exemplifies is regarded if not by the mass of men then certainly by the mass of screenwriters as an aberration, something best explained as the result of some sort of genetic defect [that chromosomal glitch, that thing that turns you into a geek] or childhood trauma. — Restraining my fury as best I can, let me state simply that if this were the case then real humans would be depressingly rare, and would have more in common with aliens than with their own species; who would consist, on this argument, of grunting apes with fewer lice. — One must wonder whether this conclusion says more about Hollywood’s view of the scientist, or Hollywood’s view of its audience.

But I probably exaggerate the power of the Dark Side. It would be fairer to say that the flick represents a reasonably successful attempt to make something relatively recondite, i.e. the real current effort to find intelligent life on other worlds, understandable to a broader audience; and that the fact that the way the story is constructed makes it in effect an exercise in talking-down is a consequence less of the bad intentions of the authors than the fact that Sagan did too much television and that Hollywood is a factory town and must almost always rely on familiar dramatic conventions to turn a profit on its product. It’s still worth seeing; not least because the peripheral characterizations are excellent. James Woods in particular is so convincing as a sinister National Security Advisor that someone ought to offer him the job.

As for the question of who I’d select to send as the sole representative of the human race to the galactic core: I’ve considered this carefully, and, if I can’t be trusted with the job myself: I want Jackie Chan.

____________Watch out for that tree (7/18/97)